Summary

Disruption is not a new concept. However, it has become the topic du jour as technological advances and shifting consumer behaviours are impacting industries and businesses. Some companies, notably pharmaceuticals, must ‘disrupt’ themselves or face irrelevance from patent cliffs every fifteen years. Others, such as car and energy companies, are facing disruption from the adoption of electric and autonomous vehicles. There are also industries where disruption is occurring but it is not being reflected in valuations. Our work on the media and retail industries, both on the frontline of disruption from the ‘FANGs’, shows that consumer staples face a less certain future, in an industry where certainty is highly valued

P&Gs brands at threat from challenger brands

Source: OP.

The rise of the internet as a new route to market for challenger brands, combined with a growing preference for private label, is hurting consumer megabrands at the point of consumption. In addition, with the decline in conventional TV viewing and the rise of digital media, challenger brands are finding it easier to take market share. All of this is leading to a fall in volumes at the large brand houses.

As patient, contrarian investors, we are constantly assessing investments for disruptive trends that are mispriced. The valuations of car manufacturers imply rapid mass adoption of electric vehicles. However, the price to earnings multiples of many consumer staples companies, at greater than twenty times and towards all-time highs, imply little chance of disruption and high expectations which may need to be reevaluated.

The virtues of consumer staples

Coca-Cola is the classic case study of how a low price, inelastic product morphed into a large global distribution base and brand portfolio. These businesses have benefited from a virtuous circle where rising volumes have driven efficiency gains in production, marketing and research. This creates barriers to entry that have been too large for new entrants to overcome. Many of the markets in which these businesses operate have become oligopolistic or duopolistic, with competition focused on minor product differentiation or advertising, rather than price.

Many of the brands we all know and love were born at the turn of the last century. However, it was not until the late 1950s / early 1960s that today's winning brands really emerged, driven by the widespread adoption of TVs. Businesses such as P&G and Coca-Cola used mass advertising to create today’s household names.

The changing market environment

These barriers to entry have been eroded over the last decade as shifts in technology and changes in consumer behaviour have affected distribution, marketing and, increasingly, product innovation.

Distribution

The initial method of distribution for the brands was convenience stores, where the brands held all the negotiating power. However, from the 1980s, convenience stores began to consolidate. For example, in the UK, the big four supermarkets increased their share of the grocery market from 40% in 1990 to over 75% at the peak in 2011.1 Retailers built considerable bargaining power to use against the brand owners.

In addition, retailers started developing private label goods to compete directly against the big brands. To date, the penetration of private label has been greatest in Europe, especially in the UK, but this trend is occurring elsewhere. The expansion of Aldi and Lidl in the US, both of which stock a very limited number of brands, may accelerate these trends.

It is the internet that has had the greatest effect on the economics of consumer staples distribution. Amazon is at the forefront of this trend, capturing 43% of all US online sales in 2016.2 It is now competing directly with major brands. Having initially started as an online retailer for 3rd party goods, it quickly developed its own products under the AmazonBasics range. Amazon now has a 15% online market share in baby wipes and a 30% share in batteries.3 This is a strategy which retailers have employed in the past (e.g. Tesco selling its own branded batteries) but Amazon has been more aggressive in its growth. It has achieved market shares that took the supermarkets decades to build. It is not just Amazon that can benefit from this new method of distribution; examples of this trend have emerged across a range of industries.

Dollar Shave Club (DSC) launched in 2011 and is focused on men’s shaving products. It started with seed funding of $1m. Sales were entirely through an online subscription model with blades being sent to customers on a monthly basis. The value proposition is compelling: Gillette, a P&G subsidiary, sells razor blades which cost $2 to $6 per cartridge, versus DSC refills which cost as little as 20 cents per cartridge. Over the last six years DSC has grown its turnover to nearly $200m.4 Gillette has seen its market share of men’s razor blades fall almost 20% and the company has cut prices by 20% as DSC and Harry’s, another challenger, gained share.5 As Michael Dubin, founder of DSC said in an interview in 2012; “this is not a business that could have worked 2½ or 3 years ago”6. In 2016, DSC was purchased by Unilever for $1bn.

Marketing

The Direct to Consumer (DTC) business model has had a material impact on the economics of distribution and access to the end consumer. Consumer goods businesses no longer need shelf space at a leading supermarket to get access to customers. DTC makes subscription-based marketing models far more viable. However, companies cannot rely solely on subscription; they still need to grab consumer’s attention.

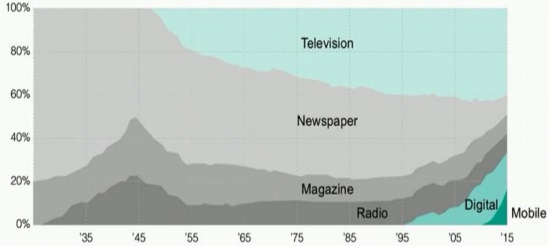

Share of advertising by medium, USA

The chart above shows the shift in advertising from print to digital over the last ten years.7 Television spend could be next to fall. Younger people are shifting their viewing pattern away from traditional TV to digital sources, where advertising is consumed in different ways.

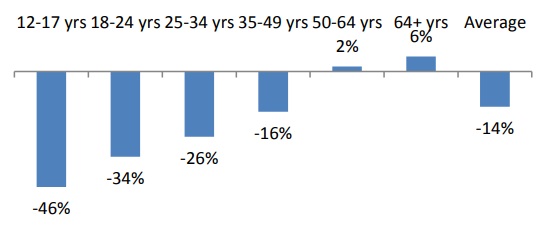

This chart shows the change in TV hours watched by different age groups over the last seven years.8 Small wonder brands have been so eager to jump on new digital platforms where Millennials are spending time. However, this trend represents a problem for the largest advertisers.

Change in hours watched of traditional TV by age group Q1 2010 to Q1 2017

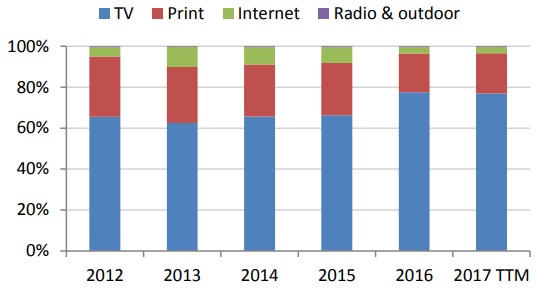

The largest brands are struggling in the shift to digital. The top 200 advertisers in the U.S. make up 80% of television advertising, despite accounting for only 51% of total advertising (41% of digital).9 P&G has actually increased its exposure to TV over recent years.10 The shift from traditional media to digital puts enormous power in the hands of Google, Facebook and potentially Amazon.

% of P&G US advertising budget

Facebook and YouTube have excellent information on who is watching what adverts and for how long, enabling them to sell highly targeted advertising at low cost. Google and Amazon offer targeted advertising based on specific search terms, something that TV could never achieve. As Sundar Pichai, Google’s CEO, said, “Our value proposition to marketers of all sizes is simple. Google can help you show the right ads to the right people at the right moment….we are seeing a major shift in consumer behaviour to its micro moments.”11 The implication is that new entrants are able to isolate key groups of consumers with limited cost, lowering the cost of entry and enabling a proliferation of niche products which target subsets of consumer groups.

In addition, social media allows people to influence each other’s purchasing habits. This can be further reinforced through Influencers. Influencers are not new. Babe Ruth, the baseball player, was endorsing tobacco brands at the beginning of the 20th century. More recent examples of celebrities using their reputation to launch brands include Jessica Alba with The Honest Company which focuses on ethical baby products, and George Clooney who co-founded Casamigos, a tequila company, which was sold in 2017 for up to $1bn.

Instagram, Facebook and YouTube enable a new breed of micro influencers with a small following to monetise their position with brands. Research from Twitter shows that 49% of Twitter users seek guidance from social media influencers prior to making a purchase.12 Word of mouth has always been a way for companies to build brands with limited advertising cost but, in the era of social media, this is becoming easier. Tesla spends about 80 bps of sales on advertising and marketing versus 350-400bps for comparable original equipment manufacturers. Dollar Shave Club reached 20 million people for less than $10,000.

Product innovation

The large brands are increasingly coming under pressure from activist investors and the consequences of zero based budgeting. This has led to a focus on incremental rather than radical innovation in order to maximise short term cash flow, despite material changes in consumer preferences over the last few years.

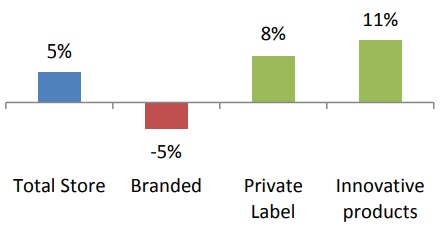

Shopping habits in UK supermarkets have shifted over the last 5 years. Brands are losing out as consumers shift to both private label and more innovative, niche products such as organic, ‘free from’ and ‘on the go’ products. The shift to alternative products has been led by specialists like Whole Foods, which was recently acquired by Amazon.

The fight back

The response from the incumbents has been to try to adopt the new entrant’s business model in parallel to their own. For example, Gillette has cut prices and is offering a subscription model. However, history shows mature businesses often struggle to execute two business models or successfully transition from one to another. Gillette has a culture and infrastructure built on TV advertising and retailer-led distribution, not the DTC social media model.

Other brands such as Nike are looking to grow their DTC model by increasing the number of own-branded stores and investing heavily in their online infrastructure. Nike has learned that customers will pay $170 for the option to customize their own products using their online sites and the company expects to increase Nike.com share of sales from 4% in 2015 to around 20% in 2020.

Acquisitions have become part of the incumbents’ response. Larger companies are snapping up smaller ones to compensate for eroding market share. Some of these investments are later stage, such as Unilever’s $1bn acquisition of DSC. Other investments try to catch the winners at an earlier stage, for example through Unilever Ventures.

Conclusion

Consumer goods brands have excellent starting positions but there is increasing evidence to suggest that their ‘moats’ are being eroded as some of these businesses are facing genuine competition for the first time in generations

The internet has been the major catalyst for new competition with disruption occurring at multiple points along the supply chain. Distribution via the internet using a DTC model and the shift from traditional to digital media is allowing brands to access more customers, in a more targeted manner, at a lower cost.

UK Supermarket volume 2013 to 2017

As a result, 90% of the top 100 CPG brands lost market share in 2015 and 60% have declining sales.13 The chart above shows these share losses are now leading to declines in volumes, not just slower growth.14

We question whether the valuation of the consumer goods sector, at greater than twenty times earnings, adequately reflects these risks. As value investors, our inclination is to focus on areas where substantial risks and low expectations are already reflected in prices, rather than where there are higher valuations and confidence in the status quo being maintained.

1. http://www.fooddeserts.org/images/supshare.htm

2. http://uk.businessinsider.com/amazon-accounts-for-43-of-us-online-retail-sales-2017-2

3. Mary Meeker: Internet Trends 2017.

4. Unilever press release 20 July 2016.

5. http://www.wsj.com/articles/gillette-bleeding-market-share-cuts-prices-of-razors-1491303601 and Euromonitor.

6. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cW8S-QBKcq4.

7. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOpSpQAxCHU.

8. Arete Research, Nielsen, MediRef * Live+VOD+DVR+TVE.

9. Advertising Age: 200 Leading National Advertisers 2015.

10. Kantar Media; TTM to Q1 2017.

11. Alphabet Q3 2015 Earnings Call

12. Twitter: New research: The value of influencers on Twitter 10 May 2016.

13. Boston Consulting Group and Information Resources (April 2016)

14. Bernstein Research