In “One-upmanship”, Stephen Potter wrote that the sure-fire rejoinder to someone saying something knowledgeable about India was “Ah yes, but not in the south.” The riposte to investment cases in a dozen industries these days is “ah yes, but what about disruption?” A potential hole in our argument that lots of companies in traditional industries have unreasonably low valuations is that technology is changing everything so that nothing traditional can be relied on. This is what is meant by disruption. A recent example was the music business, with digital replacing physical and now, within digital music, streaming replacing downloads; in the newspaper business, with both news and advertising taking to the internet; in the computer business, with smartphones taking over from personal computers and with the Cloud taking over from local servers; most painfully, perhaps, in the retail business. Robots have been displacing humans in manufacturing for years and artificial intelligence-driven systems now threaten the replacement of many ‘knowledge’ workers.

Disruption itself is not new. Wood for energy was succeeded by coal, coal by oil and gas; guns displaced bows, tanks displaced cavalry, trains displaced canals and cars displaced horses. However, there are always disruption-deniers. In 1876 Sir William Preece, chief engineer at the British Post Office, declared: ‘the Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.’ Similarly Daimler, early in the 20th century, thought that there would be need for no more than 10,000 cars because there would not be enough chauffeurs to drive them. Such forecasts are notoriously wide of the mark. McKinsey in 1986 predicted that roughly a million mobile phones might be in use by 2000. The figure was actually 109 million.

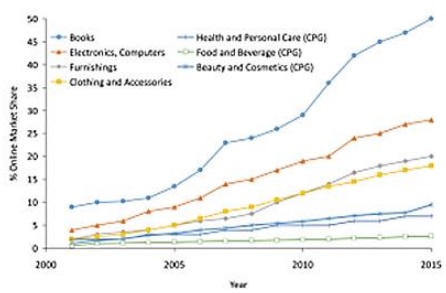

It seems obvious that the speed of obsolescence today is staggeringly fast but not everything will succeed and other ‘disruptions’ will take much longer than expected. In 1967, The Harvard Business Review published an article by Messrs Doody and Davidson that described a world of online tele-shopping, next day delivery and electronic payments. They envisioned a world where “a substantial share of staple groceries, toiletries, drugs and household supplies may be marketed through relatively few large central distribution facilities in each major market area” and that “consumers will never set foot inside these centres, except possibly for guest tours.” Their clarity of vision was remarkable but they were wrong in respect of timing. They had argued that all of the technology elements were available at the time and that they foresaw their vision becoming “commonplace sometime in the 1970’s”. Investors have shown repeatedly that they too share this foible, with investors tending to draw steep straight or parabolic lines for such transitions. While this is certainly true in some areas, like music and video, in others the gradient of the lines are much shallower, such as the replacement of the venerable mainframe computer which was forecast nearly 40 years ago and that the age of the paperless office was finally within our grasp with the launch of the iPad in 2010.

While the internet has transformed retail, its impact varies massively across the different product categories. The innovation brought by the seemingly invincible Mr Bezos has laid waste to many bricks and mortar retailers from across many categories but Amazon remains mired in losses in its efforts to “win” in online grocery. Grocery shopping is proving a very hard slog. Amazon has about 1% of the grocery market in the US, albeit a quarter of the US online grocery market some 10 years after ‘Amazon Fresh’ was launched there. Today Amazon stocks more grocery items than OPinions Oldfield Partners Walmart and with prices that match, but Amazon and its competitors have clearly struggled with the difficulties of getting bulky, relatively low value items (including chilled and frozen) to the customer when and where they want it at a cost that makes sense for both parties. With the purchase of Whole Foods, Amazon has accepted that bricks and mortar are essential for mass market grocery, at least in fresh food.

Not all disruption is fast or parabolic!

Managers like us may be thought to have an old-fashioned approach to investing which seemed once to work well but now is itself disrupted by changes in the real world that happen so fast that value investing is obsolete. To this we would say what the Harvard professor Sidney Morgenbesser said when a rival philosopher stated that while a double negative implies a positive, a double positive never implies a negative: ‘Yeah, yeah.’ It is not that there are not huge technological changes; of course there are. But the changes are not in a straight line; they are not easy to predict and they have unforeseen consequences.

The car sector is one area in which there is a lot of disruption. Mary Barra, chief executive of General Motors, has said: “I believe the auto industry will change more in the next five to ten years than it has in the last 50.” In our global portfolios we have had five investments in the automotive sector, mainly successful, since 2010: Fiat, Renault, Volkswagen, General Motors and Toyota. We still have the last two of these. Apart from the ordinary to-and-fro of economic cycles there are two technological threats to traditional carmakers: electric vehicles and autonomous or driverless cars. Investors seem only to have eyes for the obvious disruptors such as Tesla & Uber. However, this misses several points, one of which surrounds the difficulty in making lots of cars cost effectively. In its risk factors, Tesla states among many other points “we have no experience to date in manufacturing vehicles at the high volumes that we anticipate.” The mass market Model 3, unveiled in March 2016, had 400,000 pre-orders – nearly all of Tesla’s planned annual production by 2020 of 500,000 vehicles. In 2016 the company produced 84,000 vehicles. It may well succeed, but it does not have the track record to make this a safe judgement.

The incumbents are not sitting on their hands. All are building, or have plans to build, electric vehicles. Ford plans to invest $4.5 billion and introduce 13 vehicles, representing 40% of its model line-up. Volkswagen is aiming for 30 electric models to comprise more than 20% of its total sales by 2025. Tesla and others may well make significant inroads into the electric vehicle market but there is no obvious reason why the traditional carmakers should not be successful with electric cars.

Sir John Templeton’s famous aphorism was that the four (or five) most dangerous words in investing are ‘this time it’s different.’ Since only with the benefit of long hindsight will we know whether this aphorism still holds true, we stick firmly to the simple and time-tested theory that valuations are the single most important determinant of future returns. In looking at individual companies we try to be sceptics, taking time to appraise the changing fundamentals but we dispense with our view of valuations only when we see that the company’s prospects are indeed permanently disrupted – as, for example, reluctantly with Staples and with Canon. The valuations of Toyota and GM are indeed low. We do not think their prospects are disrupted. We think we will see excellent returns – as we have done already from Fiat and Renault. Other areas of the markets have other disruption complexities, but they are for another time.