Following Uber’s March 2022 quarterly results, we were particularly struck by a recent headline in the FT which read: “Uber: newfound profitability will not roll on for long”. The article went on to say: “Critically, the long-unprofitable Uber posted a positive adjusted EBITDA”.

We think the language used in the FT raises some interesting questions about what it means for a company to be “profitable”. Does it mean “positive adjusted EBITDA” as the FT article suggests?

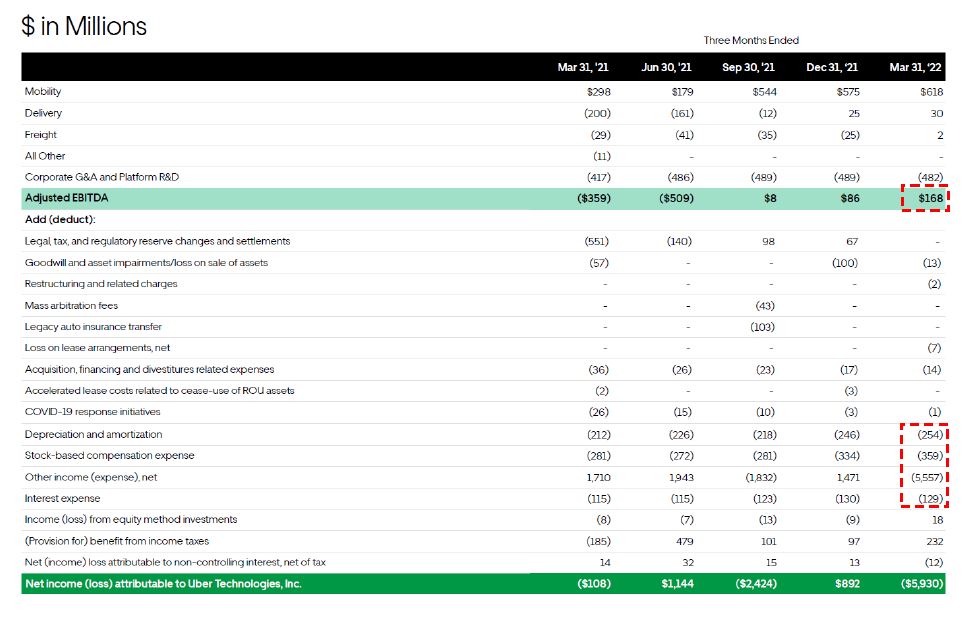

The table below shows Uber’s results for the last five quarters, including the March 2022 quarter. We can see that the company generated “Adjusted EBITDA” of $168m in the quarter which is what the FT article refers to as “profitable”.

Source: Uber Q1 2022 investor presentation, 4 May 2022

Let’s look at what goes on below “Adjusted EBITDA” to assess how profitable Uber really is. The big items are: $5,557m other expenses, $254m depreciation and amortisation (“D&A”), $359m stock-based compensation (“SBC”) and $129m interest expense. The $5,557m is mainly revaluation of equity holdings which is nonrecurring and hence we don’t consider it a real cost, so we focus on the three other items below.

D&A includes amortisation of software development costs and depreciation of leased vehicles, leased buildings, computer equipment, data centres and servers. We think these costs are just as real as any other costs we can think of. Next on the list is SBC. Between March 2021 and March 2022, Uber’s shares outstanding increased from 1,867.4 million to 1,954.6 million (+4.7%) – a shareholder who owned $100 of earnings in Uber one year ago, only owns $95 today, all else being equal. Again, we think this is a very real cost for shareholders. Next is $129m of interest expense which doesn’t need further explanation. This leaves us with $254m + $359m + $129m = $742m of very real costs before tax, dwarfing the $168m Adjusted EBITDA. To use an expression from Benjamin Graham, to call Adjusted EBITDA “profit” is to do violence either to the English language or to common sense, or both.

It is not surprising that the FT and parts of the investment community are drawn to metrics like “Adjusted EBITDA”, because this is what management teams talk about and it makes companies which aren’t profitable look profitable.

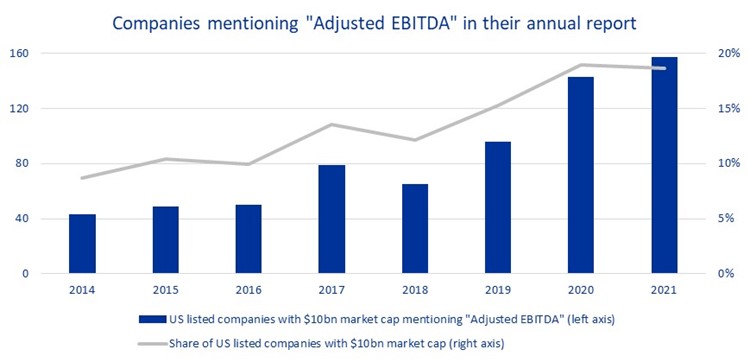

The Uber case described above made us reflect on the increasing number of references being made to metrics like “Adjusted EBITDA” in recent years. To test this we looked at the number of large (+$10bn) US companies talking about “Adjusted EBITDA” in their annual reports every year between 2014 and 2021. The results are shown below.

Source: Oldfield Partners analysis

The blue bars show the number of companies mentioning “Adjusted EBITDA” in their annual reports and the grey line shows the proportion of companies mentioning “Adjusted EBITDA”. In 2021, 157 companies mentioned “Adjusted EBITDA” which is 19% of all +$10bn US-listed companies. In 2014, the number was 43 or 9% of the total. Whilst some of the companies can justify using Adjusted EBITDA (as in some cases it is relevant when thinking about sustainable cash flows), the shift is nonetheless remarkable and reflects (i) the increasing proportion of unprofitable large companies, (ii) investors relaxing their financial discipline and (iii) management teams shifting focus away from real earnings which would make their stocks look expensive. As stocks got expensive on traditional metrics such as earnings or free cash flow, managements shifted focus to metrics like Adjusted EBITDA – and investors obliged by bidding these companies up.

This trend reminds us of what Warren Buffett wrote in the 2018 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter:

“When we say “earned,” moreover, we are describing what remains after all income taxes, interest payments, managerial compensation (whether cash or stock-based), restructuring expenses, depreciation, amortization and home-office overhead.

That brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs. Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of all-too-real costs.

For example, managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business – Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.” Abe would have felt lonely on Wall Street.”

Whilst not a prediction, we note that creative profit metrics like Adjusted EBITDA also gained popularity in the run-up to the dot.com crash. At Oldfield Partners, we go to great lengths to understand what the real earnings are of our existing investments and potential new investments. To us, real earnings translate directly into dollar bills – unlike Adjusted EBITDA. We tend to become sceptical when we see managements talking about “Adjusted EBITDA” – something which almost 20% of large US companies are talking about today.